A note about language

Readers will note that the term “Tribes” is used throughout this section specifically rather than Indigenous Nations. The language shift in this section is due to the terminology and definitions used by the FVPSA statute and regulations as it relates to eligibility to receive FVPSA funding directly from the Federal government.

The Need

Although Tribes are eligible to apply for direct FVPSA funding, there are multiple factors that underscore the need for States to make State FVPSA subawards available to Tribes.

Tribes and tribal organizations are eligible subrecipients of the mandatory FVPSA funding received by States even if the Tribes and tribal organizations are already receiving FVPSA funds directly. Both Federally recognized and State recognized tribes are eligible to apply for pass through FVPSA funding from a state. States have the authority to utilize their own grant awards processes as long as they comply with Federal statutes and regulations per 45 CFR § 75.327 of the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for HHS Awards.

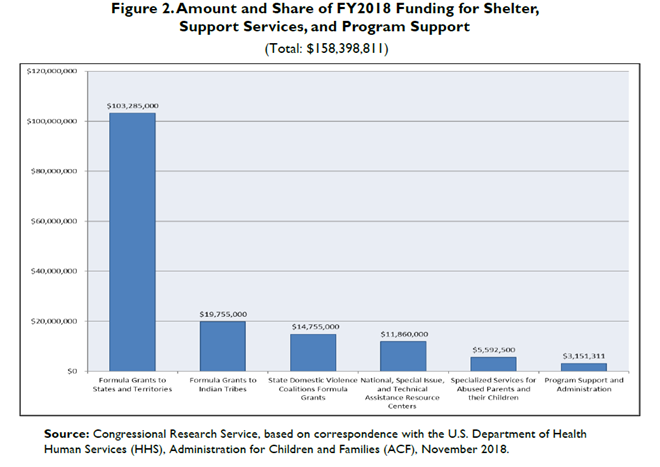

It is important to remember that Tribes only receive 10% of the available FVPSA funding directly compared to the 70% that States receive (see chart below from Congressional Research Service). Additionally, the funding is only available to federally recognized tribes. There are multiple populations who still need access to life saving domestic violence funding including State recognized Tribes, Tribes fighting for state or federal recognition, and indigenous communities/populations. States have an opportunity to help meet this need through the provision of subawards with State FVPSA funds.

Source: Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA): Background and Funding. Updated April 4, 2019. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov. R42838

Like the tribal allocation described in the Federal FVPSA Funding Overview section, the allocation percentage (70%) that States receive from FVPSA is distributed through a formula that includes funding through a base component plus a population component based on the U.S. Census. Tribal community members are also residents of the state, and the State’s population numbers include Tribal populations which makes them eligible to apply to the state for funding.

Despite common misconceptions, Tribes often do not have the resources available to fully fund domestic violence programs. With funding under FVPSA many Tribes have developed tribal programs to provide a spectrum of services, including: shelter, safety planning; counseling; legal services; child care and services for children; career planning; life skills training; community education and public awareness; and other necessities, such as clothing, food, and transportation. Yet, despite the advances, funding and services remain nonexistent for over one half of all Indigenous nations. For some tribes federal FVPSA funds may be the only available source of funding. Historically low awards, a lack of other available funding, and high rates of economic disparity has meant many Tribes can only provide limited services. Shelter may only be provided through hotels/motels or safe homes, and/or Tribes may only be able to provide non-residential supportive services such as advocacy, transportation to non-native shelters, or counseling. According to a June 2021 article in NIWRC’s Restoration Magazine, there are only 58 Native domestic violence shelters nationwide compared to 1,673 non-Native shelters. Yet, American Indian and Alaska Natives experience higher rates of violence than any other population according to the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) study as seen in this video.

In reviewing the State FVPSA FOA, States will notice the emphasis FVPSA places on States ensuring funding availability for Tribes under I. Program Description: Coordinated and Accessible Services. Additionally, in section IV. Application and Submission: The Project Description, States are required to provide detailed information in their applications regarding the names, numbers, and funding levels provided to tribes. States must be careful to ensure they are funding Tribes and/or tribal organizations.

Funding a non-Native domestic violence non-profit that is located on or near a Reservation and/or who provides services to Tribal survivors is not the same as funding a Tribe or tribal organization.

Unless a Tribe has issued a Tribal Resolution or equivalent document that expressly designates a non-profit to receive and/or manage their funds, simply funding such non-profits will not meet FVPSA’s goals. It is also important to remember that even if the State is utilizing other State or Federal funds to provide grants to Tribes that does not relieve them of the responsibility to make FVPSA funding accessible to Tribes and tribal organizations.

Accessing State FVPSA Funds

As described in the Need section, federally recognized and state recognized Tribes and tribal organizations are eligible subrecipients of the mandatory FVPSA funding. Each state has their own procurement process for the selection and distribution of FVPSA funding. State Administrators should ensure they are engaging in meaningful collaboration and ensuring the State is connecting with Tribes and tribal organizations, notifying them of funding availability, ensuring the process involved in applying is accessible to Tribes and tribal organizations, and ensuring the process for applying is fully explained. If Tribes and Tribal organizations have any additional questions, they can contact their State Administrator office for details.

The FVPSA statute mandates states to provide subgrants to eligible entities at 42 U.S.C. §10406(b)(2). Eligible subgrantees are listed at 42 U.S.C. § 10408(c) of the FVPSA statute:

To be eligible to receive a subgrant from a State under this section, an entity shall be—

(1) a local public agency, or a nonprofit private organization (including faith-based and charitable organizations, community-based organizations, tribal organizations, and voluntary associations), that assists victims of family violence, domestic violence, or dating violence, and their dependents, and has a documented history of effective work concerning family violence, domestic violence, or dating violence; or

(2) a partnership of 2 or more agencies or organizations that includes*—

(A) an agency or organization described in paragraph (1); and

(B) an agency or organization that has a demonstrated history of serving populations in their communities, including providing culturally appropriate services.

While this does not mean that states are required to fund every eligible tribe/entity/organization, they are expected to make the application process, funding instruments, and contracts as accessible and low barrier as possible for all eligible entities, including Tribes and tribal organizations.

*Note: The partnership between two or more agencies as described in the FVPSA statute pertains to who is eligible to receive State FVPSA pass-through funds as a subrecipient. The partnership referenced in the statute is a separate definition from the definition for Tribal Consortium in the Tribal FOA. As described in the Tribes and Federal FVPSA Funding: Tribal Consortiums section, Tribes who apply as part of a consortium for Federal FVPSA funds, may also apply for FVPSA funding through their State as an individual entity, as part of the partnership described in the FVPSA statute, or as a part of a state consortium process if available as the state processes and funding streams are completely separate from the Federal processes and funding stream.

Ensuring Accessibility to State FVPSA Funds

Accessibility to State FVPSA funds for Tribes and tribal organizations is imperative. State Administrators must strive to make each step of the process as low barrier as possible. By thoughtfully reviewing each step well in advance, States can ensure their disbursement of funding is in compliance with Federal statutes and regulations.

It is important to remember that Tribes are sovereign nations, and each Tribe operates with their own set of laws and processes. There is no “one size fits all” approach, and there may be a need for a more formal tribal consultation process. State administrators must examine the funding requirements and grant process in collaboration with Tribal Coalitions, Tribes and tribal organizations, and culturally specific organizations to identify, understand, and remove/reduce the barriers these eligible entities are facing. State administrators are also encouraged to reach out to their State Domestic Violence Coalition, FVPSA Project Officer and FVPSA TA providers in the DVRN to review and provide feedback on the accessibility of the application, including the process, any award instruments, and methods for engaging with and consulting with Tribes and tribal organizations in their state. The examination of funding requirements and meaningful collaboration with State and Tribal Domestic Violence Coalitions are not only best practices, but are key components of the FVPSA required State Domestic Violence Coalition Needs Assessments and State Planning processes.

States may find the following list of questions helpful as they review funding instruments, consider announcement processes, and contracts. These questions are not an exhaustive list, and States are encouraged to include additional questions to ensure full accessibility.

- Are Tribes and tribal organizations specifically listed as eligible entities to apply?

- Is the information about the availability of funding reaching the Tribe/tribal organization (i.e. are a variety of contact/announcement methods used)?

- Is there sufficient time for a Tribal DV program to obtain approval from Tribal Council to apply for funds?

- Every tribe operates differently and some have faster processes than others. States should collaborate with the Tribes and Tribal Coalition to understand the timeframes for each of the Tribes in their state and adjust their application process accordingly.

- Does there need to be a competitive process or is there another process that allows the State to enter into a direct contract with the Tribal government?

- Is there a requirement to be a non-profit?

- Is the language throughout the funding instrument geared towards tribes or non-profits?

- Are there requirements to operate a shelter?

- See description of Tribal services under The Need section

- Are there state standards or licensing requirements included that don’t fit Tribes and tribal organizations needs/capacity/sovereignty?

- To understand the impacts of standards or requirements, convening a focus group of Tribes, Tribal organizations, Tribal Coalitions and/or the State DV Coalition, may be necessary, and is required under state needs assessment and planning requirements as described in FVPSA regulations at 45 CFR § 1370.10 (a).

- Are there requirements to be members of the State Domestic Violence Coalition?

- FVPSA statute states that Tribes and tribal organizations are eligible members at 42 U.S.C. § 10411(h), and membership invitations should be sent to Tribes. However, with regard to Tribal sovereignty, the decision to join the State Domestic Violence Coalition as a member is solely the Tribe’s decision.

- Are there restrictions on “service areas”?

- Remember:

- Reservations and indigenous lands may not align with State and County borders

- Indigenous populations may be located just outside of a State or County defined area, but within range of Tribal or culturally specific services where survivors may be more comfortable receiving services

- Is there a lot of paperwork and other documentation requirements that involve more time/effort than the amount of funding provided?

- While some paperwork and documentation requirements may be required under a State’s procurement laws, there may be other areas where State administrators have flexibility. As part of the FVPSA required needs assessment and state planning processes, State Administrators and Coalitions should engage in meaningful collaboration with Tribes, Tribal organizations, and Tribal Coalitions to understand the impact of the application and post award processes and work together to amend processes as necessary and mutually agreed upon.

- Does the application process allow for paper applications for those in remote areas/those with limited internet or computer functionality?

- Does the application allow for culturally responsive services?

- Is the funding amount equitable?

- Equitable does not always mean equal “slices of the pie.”

State administrators should consider holding an informational session prior to the release of the grant applications. The sessions should be developed in collaboration with Tribal Coalitions and State DV Coalitions to assist in the identification of potential grantees the State may not have worked with previously and to ensure the information is accessible and responsive to the needs of eligible applicants. The sessions will allow potential grantees to learn about the application and the reporting processes.

Informational sessions are just one component to consider. Understanding the needs of tribes and indigenous communities should be an ongoing process that is woven into statewide needs assessments and state planning processes. In order for such processes to be successful, states and state domestic violence coalitions must participate in meaningful collaboration with tribes, Tribal coalitions, and underserved communities. One session or one session every few years is not enough time to truly build relationships or adequately understand the needs of tribes and indigenous communities. Such methods will not only fail to demonstrate that the state and statewide domestic violence coalition are meeting the requirements of FVPSA, but they will also reflect a disingenuous attitude and could undermine and damage relationships with tribes and indigenous communities and ultimately harm Native survivors.

Meaningful Collaboration

Meaningful Collaboration is an ongoing process where there is intentional and thoughtful engagement between parties to safely share information and exchange ideas in order to come to a mutual understanding that will lead to informed decision making by all parties to address common goals. Such collaborations are held by a foundation of trust made up of several key components including active listening, respectful discussions, upholding commitments, and taking responsibility for actions. While the goals of meaningful collaboration sound simple, such partnerships take both time and substantial effort. Parties will not always agree, but there is room to agree to disagree. However, disagreements must also take place within the confines of the foundation of trust. Failing to utilize any one of the key components will harm the process and potentially damage relationships.

It’s important to remember when working with tribes and underserved communities that there may be cultural differences in communication, practices, and customary interactions. Western culture is often reflected by states and state domestic violence coalitions, and may even be different from what we as individuals know and practice from our own cultures. Tribes are not monolithic in their culture and customs or governmental structures and operations, and what works with one tribe may not work or could be offensive to another. Taking the time to learn about cultures and customs and genuinely getting to know the tribes and communities states and state domestic violence coalitions will be working with is a key component to building strong relationships.

As states and state domestic violence coalitions work to build relationships and engage in meaningful collaboration, mistakes will happen. Mistakes are part of the human experience and are not bad in and of themselves, but how parties respond to the mistake is what is critically important. Taking responsibility for actions when mistakes are made as well as engaging in active listening and respectful discussions are key to moving beyond the mistake. Remember, engaging in the key components of the foundation of trust are integral in maintaining meaningful collaboration. Ensuring the key components of the foundation of trust are utilized when mistakes are made will not only assist in moving beyond the mistake but will continue to strengthen relationships and trust. While mistakes may happen no matter how well prepared we try to be, below are some scenarios to avoid that demonstrate what meaningful collaboration is not and questions to consider about the scenario:

- A state administrator is hosting a state planning session and sends an email invitation for the date to a local tribe they have not previously worked with. When no one shows up the state assumes the tribe is not interested in participating.

- Did the email invitation go to the correct person?

- What is the history of the state’s interactions with that tribe?

- Did the state administrator introduce themselves, their role, explain the purpose of the meeting, and explain why they are inviting the tribe?

- Did the state ask if the date would work for the tribe and offer to change the date or host additional dates if it didn’t work?

- Did the state follow up after the meeting to see how they might connect in other ways?

- A state administrator is hosting a state planning session and sends an email invitation for the date to a representative from an indigenous community that they have been working with for the last year and a half. At the planning meeting, the state explains to the attendees what their goals, plans, and next steps are that they will be taking. When the representative from the indigenous community makes a suggestion, the state thanks them but says they are too far in the planning process this year and will have to address it the following year.

- Did the state consult with the indigenous community to find out their needs and suggestions prior to developing their goals, plans, and next steps?

- Did the state consider how they may need to adjust their goals, plans, and next steps to ensure that the indigenous community’s needs are met?

- Did the state engage in respectful discussions about why the indigenous community made the suggestion to find out more about it?

- If the indigenous community had not made a suggestion, was the state planning to check in with them outside of the meeting to find out if there were any concerns that should be addressed?

- Did the state really intend on engaging with the indigenous community in a meaningful way or were they “checking a box” for who had a seat at the table?

- A state domestic violence coalition has asked a tribe to co-host a listening session for the statewide needs assessment. The state domestic violence coalition tells the tribe they will need to contribute $1500 from their Federal FVPSA grant to help cover the costs of food, supplies, and the meeting space.

- Did the state domestic violence coalition previously ask the tribe if they would contribute funding?

- Did the state domestic violence coalition collaborate with the tribe on the planning of the session prior to demanding funding contributions and jointly agree if costs would be incurred and what kind?

- Did the state domestic violence coalition have a previously established contract with the tribe detailing an exchange of money and roles and responsibilities of each party?

- Did the state domestic violence coalition have a previous discussion with the tribe and understand if the tribe had funding availability in their budget for this type of cost and discuss whether the tribe was able and willing to contribute their funding?

- Did the state domestic violence coalition make assumptions about the tribe’s use of their own funding?

- A representative from a tribe reaches out to their state domestic violence coalition and expresses interest in becoming a coalition member. The state domestic violence coalition provides the representative a list of application guidelines, including requirements that would be challenging for the tribe to meet given their governance structure. When the tribe asks the state domestic violence coalition about the requirements, the state domestic violence coalition says tribes aren’t eligible for full membership as they are not a non-profit, domestic violence organization.

- Did the state domestic violence coalition review the FVPSA regulation requirements around the eligibility of tribes to become state domestic violence coalition members?

- Has the state domestic violence coalition recently examined their membership requirements to determine accessibility?

- Has the state domestic violence coalition considered removing or adjusting requirements that prohibit tribes or other underserved communities from joining the membership such as due structures (are they equitable for all size programs, tribes, or other organizations?), requirements to be a non-profit, requirements to be state or federally funded programs, etc.?

- Has the state domestic violence coalition made a commitment to be more inclusive so that the needs of all survivors in the state are met?

- Has the state domestic violence coalition made a commitment to have the board, membership, and staff be truly representative (i.e. not just “checking a box”) of the populations they serve?

- Note: this is also a requirement under FVPSA regulations for memberships and boards

States and state domestic violence coalitions that make a commitment to building and strengthening relationships with tribes, indigenous communities, and other underserved communities will benefit from engaging in meaningful collaboration and will be better prepared for successful state planning and statewide needs assessments processes.